Army Aviation: Above the Best

From the Air Force Split to the Modern Battlefield: A Brief History of Army Aviation

In September 1947, the U.S. Air Force was established as an independent service, severing the Army Air Forces from the Army’s command structure. With the Key West Agreement of 1948, the Army was left with only a handful of light fixed-wing liaison planes (such as the L-2 Grasshopper) to support ground units. However, this post-WWII limitation laid the groundwork for a new kind of Army Aviation, centered on the helicopter. In 1947, the same year of the Air Force split, the Army acquired its first batch of Bell H-13 Sioux helicopters. These early rotary-wing machines showed promise during the Korean War (1950–1953), performing medical evacuations (MEDEVAC) from frontline aid stations and ferrying commanders and critical supplies across rugged terrain. The Korean experience proved that helicopters could go where fixed-wing aircraft could not, sparking a rivalry with the new Air Force over roles and missions in the sky.

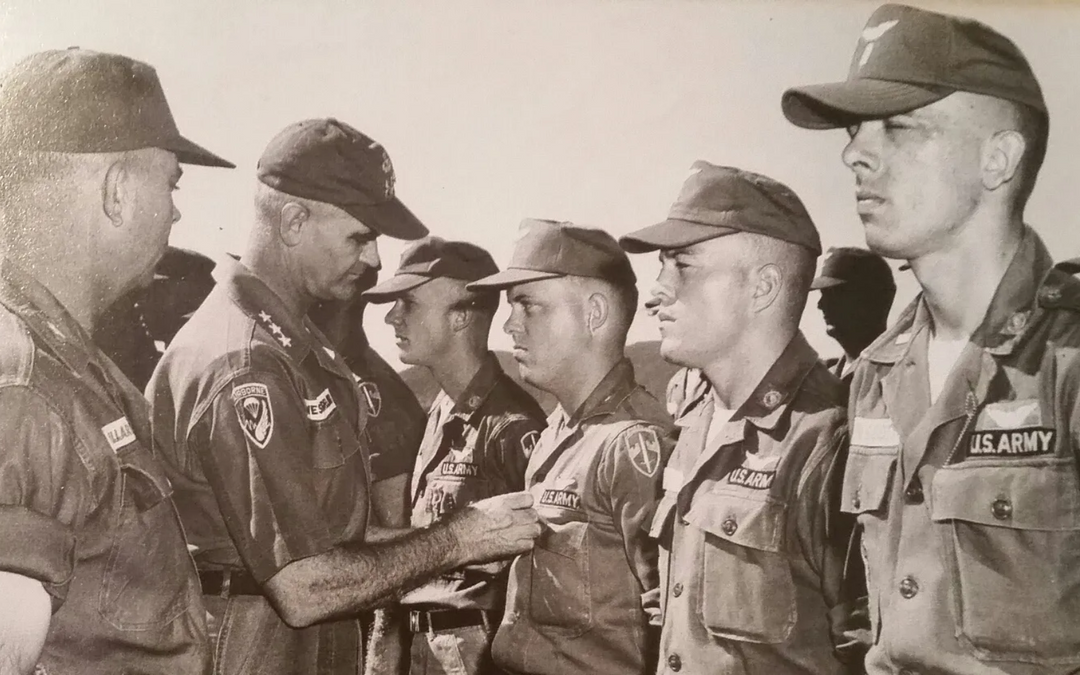

Throughout the 1950s, Army Aviation slowly expanded. The Army began training warrant officer pilots and stood up its first helicopter transport companies. Still, the Army was technically restricted from operating armed or heavy aircraft. That changed in the early 1960s. In 1962, the Army convened the Howze Board, officially the Tactical Mobility Requirements Board, which developed the revolutionary concept of air mobility: using fleets of helicopters to maneuver infantry and firepower around the battlefield. The Howze Board’s recommendations were put to the test with the 11th Air Assault Division (Test), and in 1965, the famed 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) deployed to Vietnam as a fully helicopter-mobile force. During the Vietnam War, often called “America’s Helicopter War,” icons like the Bell UH-1 Iroquois (“Huey”) became ubiquitous. Over 5,000 Hueys were deployed to Vietnam, ferrying troops into combat assaults, evacuating wounded under the call sign “Dustoff,” providing close air support as gunships, and revolutionizing how the Army fought. The first dedicated attack helicopter, the Bell AH-1 Cobra, also made its debut in 1967, proving the concept of helicopter gunships escorting transport helos into landing zones.

By the war’s end, the helicopter had secured its place as an indispensable asset to Army operations. A 1966 inter-service agreement (the Johnson-McConnell Agreement) formally limited the Army to rotary-wing and small fixed-wing aircraft only, ceding the jet age to the Air Force. Undeterred, the Army focused on perfecting its vertical lift capabilities. The 1970s and 1980s saw a wave of modernization: introduction of the Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk to replace the aging Huey, the advanced Boeing AH-64 Apache attack helicopter, the CH-47 Chinook upgraded to modern standards, and specialized scouts like the OH-58D Kiowa Warrior. Equally important, after decades of debate, the Army officially created the Aviation Branch on April 12, 1983. Army Aviation was now a basic branch of the Army (no longer just an auxiliary function), consolidating all aviation training, personnel management, and doctrine under one proponent at Fort Rucker. This reorganization reflected how large and technologically sophisticated Army Aviation had become since the 1940s.

Army Aviation played decisive roles in late-Cold War and post-Cold War conflicts. In Operation Just Cause (Panama, 1989) and Desert Storm (Iraq, 1991), Apache attack helicopters spearheaded nighttime assaults. Famously, Apaches knocked out enemy radar sites in the opening minutes of Desert Storm. Helicopter units provided unmatched agility, striking targets at night and rapidly shifting troops across the battlefield. The 1990s drawdown after the Cold War led to restructuring (the Aviation Restructure Initiative) and the retirement of older aircraft. By the 2000s, Army Aviation was adapting to new missions, including peacekeeping in the Balkans, high-altitude flying in Afghanistan, and intensive urban operations in Iraq. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) were brought under Army Aviation oversight in 2003, integrating drones alongside manned helicopters to provide reconnaissance and targeting support. Today, Army Aviation remains the crucial “vertical maneuver” element of the force, finding, fixing, and destroying enemies from the air while rapidly moving friendly troops and supplies as part of the combined-arms team.

Technological advancement continues. The venerable helicopters of the late 20th century are now being gradually replaced by next-generation designs. In 2022, the Army awarded a contract for the Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft (FLRAA) to Bell Textron’s V-280 Valor, a tiltrotor craft expected to replace the Black Hawk in the 2030s. This high-speed, long-range platform, part airplane and part helicopter, promises to fly farther and faster than any previous Army rotorcraft, extending the reach of air assault missions.

Origin, Meaning, and Evolution of the “Wings”

Following the Air Force's split in 1947, the Army required a new insignia for its remaining pilots. The result was the creation of the Army Aviator Badge in 1950, essentially a modified version of the pilot wings that had been used by the old Army Air Forces. On July 27, 1950, the Army approved the Aviator Badge (for pilots) and a Senior Aviator Badge, followed by a Master Aviator Badge on February 12, 1957. These mirrored the Air Force’s three-tier system of pilot wings (basic, senior, command) but with distinct Army styling. Interestingly, throughout the 1950s, the Army still issued the former Aircrew Badge (a winged propeller emblem from WWII) to non-pilot flight crew. It wasn’t until May 1962 that a unified design was adopted: the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations approved a redesign of Army aviation wings, renaming the Aircrew Badge to the “Aircraft Crewmember Badge” and standardizing the look to what we recognize today. The new insignia, a pair of outstretched wings flanking a central shield, would henceforth be issued in three degrees (Basic, Senior, and Master) to reflect an individual’s level of flight experience.

Design & Symbolism

Every element of the badge’s design carries meaning. The badge consists of a pair of oxidized silver wings extending from a central shield. According to the U.S. Army Institute of Heraldry, “The wings suggest flight and reflect the skills associated with aerial flight,” while the shield signifies “loyalty and devotion to duty.” In other words, the wings celebrate the flying craft of the aviator, and the shield roots that skill in service to country. As an aviator progresses in seniority, additional symbols are added above the shield: a five-pointed star for a Senior Aviator, and a star encircled by a laurel wreath for a Master Aviator. The star denotes the higher qualification and experience of senior aviators, while the laurel wreath, a classical symbol of achievement and honor, crowns the master-level wings to indicate the pinnacle of aviation expertise. All three grades share the same fundamental appearance aside from these devices.

Levels and Criteria

The Aviator Badge hierarchy has three levels: Basic, Senior, and Master. Earning the Basic Aviator Badge requires graduating from the rigorous Army flight training program and being formally designated as an Army Aviator on orders. This is the set of wings every newly minted pilot receives upon “winging”. To further recognize experience, the Army set down specific requirements for the advanced badges. Historically, a Senior Army Aviator needed at least 7 years of rated aviation service, 84 months in operational flying assignments, and a minimum of 1,000 flight hours as a pilot. Likewise, a Master Army Aviator (sometimes informally nicknamed “Master Wings”) has at least 15 years of service, 120 months in operational flying, and 2,000 flight hours in their records.

Alongside the Aviator Badge worn by rated pilots, the Army also recognizes the essential contributions of non-rated personnel, those who serve in aviation roles but aren’t pilots, through the Aviation Badge. Over time, the Army has adjusted who is eligible to wear these aviation badges. In 2000, the “Aircraft Crewmember Badge” (for non-rated crew) was renamed the Army Aviation Badge, and its award criteria were broadened. Previously, only soldiers on actual flight status (logging flight hours) could earn senior or master wings. For example, a crew chief could qualify by accumulating a certain number of flight hours over the years. After February 29, 2000, the Army eliminated the flight-hour requirement for crew badges and instead made the badge a mark of one’s Aviation career field as a whole. Now, any soldier who graduates from an Army aviation MOS school (whether as a helicopter repairer, crew chief, or UAV operator) is awarded the Basic Aviation Badge, and the Senior/Master levels are tied strictly to years of service in the aviation field (7 years for Senior, 15 for Master, with slightly longer timelines if the soldier wasn’t on flight status).

Conclusion

Over the decades, U.S. Army Aviation has continually reinvented itself, from the humble Piper Cubs spotting artillery in the 1940s, to the Hueys and Cobras dominating jungle skies in the 1960s, to the Apaches and drones of the 21st century and beyond. Through it all, the Army Aviator Badge has remained a constant, winged reminder of the human element at the heart of this story: the pilots and crew who devote themselves to mastering flight and supporting the mission. Those oxidized silver wings symbolize not just an individual qualification, but the heritage of an entire community that calls the sky home.

Above the Best

Leave a comment