Bristling at Authority: The Mustache Tradition in Military Aviation

It is a crisp morning on a World War I airfield, and a young pilot tightens his flying scarf. On his upper lip sits a proud mustache, waxed and curled at the tips. Equal parts fashion statement and good-luck charm. Decades later, over the skies of Vietnam, another aviator strokes a far bushier handlebar mustache before strapping into his jet, defying regulations with a grin. From the earliest days of flight, the mustache has ridden shotgun with military aviators, growing into a symbol of daring, rebellion, and camaraderie. This is the story of how a bit of facial hair became woven into the cultural fabric of military aviation, from the Great War’s flying aces to modern-day fighter pilot traditions.

Whiskered Knights of the Sky: Early Aviators and Their ‘Staches

In the early 20th century, a well-tended mustache was practically part of the uniform for many military men, and aviators were no exception. In fact, the British military had mandated mustaches for soldiers since the 19th century. A Victorian-era regulation forbade British Army personnel from shaving the upper lip at all, effectively making mustaches compulsory until 1916. This decree was eventually dropped during World War I, but by then, the mustache had already become emblematic of martial virility and daring. Early pilots inherited this ethos. The archetypal British flying ace of World War I and into the 1920s sported a dashing ‘stache (think waxed tips peeking from under a leather flying helmet) as if to proclaim both gentlemanly breeding and devil-may-care bravery in one flourish.

Some of the first heroes of aviation wore their mustaches with pride. French aviator Louis Blériot, who conquered the English Channel by air in 1909, was nearly as famous for his luxuriant whiskers as for his airplane. In the United States, Orville Wright donned a thick “Chevron” mustache from his youth, which he kept neatly trimmed even as he made history at Kitty Hawk. In photographs, Orville’s reddish mustache curls over his lip, an almost whimsical contrast to the serious business of inventing flight. These early aviators’ facial hair wasn’t just fashion; it linked them to a long military tradition of the mustachioed warrior, lending an air of seasoned authority even to men exploring a brand-new frontier.

By World War II, the mustache was firmly entrenched as part of the aviator image, nowhere more so than in Britain’s Royal Air Force. The RAF continued the Great War custom with gusto. Regulations in the RAF during WWII even stated “the whole of the upper lip shall remain unshaven,” underscoring how integral a mustache was to the aviator’s look. It wasn’t technically a requirement by then, but in practice, the flamboyant fighter pilot’s mustache became iconic. Handlebar styles were especially popular, since King’s Regulations only allowed mustaches that did not drop below the upper lip line, prompting creative flyers to grow them outward and upward instead. Many of the Battle of Britain’s celebrated pilots can be seen in photos with trim mustaches or impressive handlebars, contributing to the archetype of the jaunty RAF aviator with a steely gaze and a “furry friend” under his nose. As one tongue-in-cheek historian noted, “the archetypal RAF fighter pilot of the Second World War wore one.” The mustache conveyed a certain dashing insouciance and was thought to embody the service’s esprit de corps.

Wing Commander Robert Stanford Tuck ‘Tuck shop’

Across the Atlantic, American military aviators of the WWII era were generally more clean-shaven, partly reflecting U.S. Army regulations emphasizing a neat, uniform appearance. Beards were banned in the U.S. forces (to ensure gas masks fit properly), but mustaches were still permitted within strict limits. However, flamboyant facial hair never quite took root in the American military the way it did in the RAF. The prevailing style for U.S. Army Air Forces pilots during WWII was clean-cut professionalism.

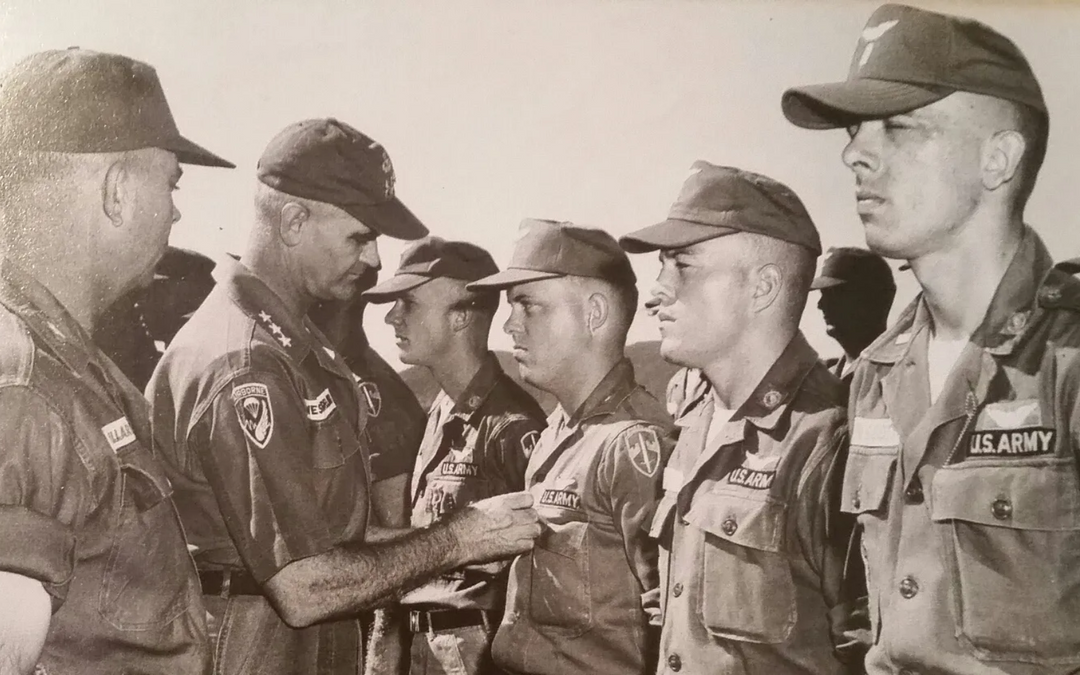

The Rebel ‘Stache Emerges: Robin Olds and the Vietnam Era

If the classic RAF mustache embodied tradition and unity, the mustaches that took root in the Vietnam War era added a new meaning: open rebellion. In the 1960s, U.S. Air Force regulations on appearance were strict. Clean-shaven faces were the norm for stateside Airmen. But in the combat zones of Southeast Asia, some pilots began bending those rules. It became a common superstition among aircrews in Vietnam to grow a so-called “bulletproof mustache” for good luck, as if the hair on their lip could somehow ward off enemy fire. Most kept their mustaches within regulation length, but a few pushed the boundaries, nurturing ever-bushier growth as tours went on. The mustache was turning into a quiet act of defiance against the buttoned-up military rulebook, especially for the fighter jocks whose very job demanded aggression and independence.

"Wolfpack" aviators of the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing carry Olds, following his return from his last combat mission over North Vietnam, on 23 September 1967

No one carried the banner (or rather, grew the mustache) of defiance more famously than Brigadier General Robin Olds. Olds was a triple ace, a legendary pilot with kills in WWII and Vietnam, and by the time he took command of the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing in 1966, he was already regarded as a maverick. In Vietnam, Olds let his inner rebel flourish in the form of an extravagantly waxed handlebar mustache that blatantly flouted Air Force grooming regs. As he later quipped, “It became the middle finger I couldn’t raise in the PR photographs. The mustache became my silent last word in the verbal battles…with higher headquarters on rules, targets, and fighting the war.”

Olds didn’t invent the idea of a fighter-pilot mustache, but he gave it new rebellious glory. Initially, he started growing it as a friendly challenge. As Olds recounted, one night in 1966, he joked with a younger pilot who had a tidy regulation mustache about how he might look with one himself. One thing led to another, and the 44-year-old colonel began cultivating his own lip sweater. It started within the rules, but after Olds’ F-4 Phantom squadron scored a major victory against North Vietnamese MiGs in Operation Bolo in January 1967, he decided the mustache had earned a promotion of its own. He let it grow wild and beyond regulation, styling it into a dramatic swooping handlebar that could be spotted from a mile away. “What was anybody going to do,” he joked, “send the Secretary of the Air Force over to knock me down and shave it off?” The men under his command loved it. Olds’ brash mustache became a signature of the 8th Fighter Wing “Wolfpack,” a totem of their unit pride and wartime superstitions. Indeed, many of Olds’ pilots grew their own “Wolfpack mustaches” in emulation, a visible, hairy bonding ritual in the face of danger. The unit’s camaraderie (and daredevil success in the air) only grew alongside the mustaches.

By the time Olds finished his Vietnam tour in late 1967, his flamboyant facial hair had taken on almost mythic proportions. There was, however, one person not amused: General John P. McConnell, the U.S. Air Force Chief of Staff. When Olds returned stateside for an assignment at the Pentagon, he strode into a meeting with McConnell still wearing his now-famous cookie duster. The bemused tolerance Olds had enjoyed in the war zone evaporated. As Olds told it, McConnell walked up, placed a finger under Olds’ nose and curtly ordered, “Take it off”. That was the end of the mustache, officially at least. Olds dutifully shaved, later admitting privately that “I wasn’t all that fond of the damned thing by then” but understood it had become a “symbol for the men of the 8th Wing” and had to run its course.

What happened next would spark an Air Force legend. Upon hearing that their icon, had been forced to shear his mighty ‘stache, aviators around the world reacted in solidarity by growing their own mustaches out en masse. In a tongue-in-cheek display of protest, pilots and crew from Vietnam to bases in Europe started sporting unapologetic mustaches as if to say, “If our hero has to shave, we’ll grow what he no longer can.” This spontaneous groundswell coalesced into what is now known as “Mustache March.” The tradition, credited as beginning with Olds’ post-Vietnam shave in 1967, invites Air Force personnel each year to spend the month of March growing out their mustaches in a good-natured rebellion against strict grooming rules. What started as pilot folklore is now an institutionalized bit of Air Force culture, one that brings together everyone from young Airmen to four-star generals for some fuzzy upper-lip camaraderie each spring.

Capt. Mike Beachamp, 434 Flying Training Squadron instructor pilot, poses in front of the Brig. Gen. Robin Olds inspired SCAT VI aircraft - Laughlin Air Force Base, Texas, Jan. 22,2021.

Robin Olds’ mustache has since become the stuff of legend. Displayed in museum photos, celebrated in songs (yes, there’s a fighter pilot folk song about Mustache March), and revered as a symbol of a warrior who bucked the system just enough to keep his edge. It showed that even in a highly disciplined organization, there was room for individuality and even a bit of rascality, especially among those daredevils who streak through the skies. As one Air Force historian put it, Mustache March and the cult of the fighter-pilot ’stache represent “some damn pilot thing” that outsiders may smile at, but insiders cherish as a link to one of their greatest Airmen.

Regulations vs. Rebels: Grooming Standards and Workarounds

The long love affair between aviators and mustaches hasn’t always been a smooth ride (just ask any Army pilot). It exists in tension with military grooming regulations that, by design, frown on excess facial hair. All branches of service impose rules aimed at uniformity, hygiene, and the ability to properly wear equipment like oxygen masks and respirators. Generally, modern regulations permit a neat mustache (with a laundry list of exact specifications), but nothing more. For example, the U.S. Air Force today allows mustaches as long as they are “conservative” in style and do not extend beyond the corners of the mouth or cover the upper lip line. The wording is almost comically precise: a mustache, in official parlance, must be “tapered, trimmed, and tidy” and definitely not waxed into handlebars or grown bushy enough to be deemed “extreme.” Meanwhile, beards are still prohibited for most Air Force and Army personnel (except by waiver for medical or religious reasons), a legacy of policies dating back to World War I when clean-shaven faces improved gas mask seals.

Given these tight constraints, one might assume the pilot mustache tradition would have withered over time, but aviators are nothing if not resourceful in bending rules. Many have treated the regs as a challenge: how to grow the most impressive mustache within the letter of the law. Thus was born the art of the “regulation-max” mustache – grown right up to the limits of width and thickness allowed, but no further. In practice, this means many U.S. pilots cultivate a bushy caterpillar that spans the width of the mouth and maybe just barely stays above the lip line. (The more cynical might note that some commanders turn a blind eye to slight excess during Mustache March or deployments, so long as discipline is otherwise maintained.) Aviators take pride in these little loopholes. It’s a way to assert individuality in an institution built on conformity: Yes, we will follow your rules, but we’ll do it with style.

Sometimes, rule-bending turns into open conflict. A famous case from 2008 illustrates how deeply the mustache tradition is valued and how far aviators will go to defend it. That year, Royal Air Force Flight Lieutenant Chris Ball, on exchange with a U.S. Air Force fighter squadron in Afghanistan, reported for duty wearing a magnificent handlebar mustache stretching a full six inches from tip to tip. Such a “full-length tash,” as the Brits might say, was well outside U.S. regulations. Sure enough, an American general ordered Flt Lt Ball to trim his whiskers to a more “manageable” (i.e. American) size. The RAF pilot was having none of it. In true Biggles-esque fashion, he cited Queen’s Regulations, which happened to have no upper limit on mustache width so long as the ends didn’t droop below the edge of the mouth. Ball carefully measured his handlebars, found they complied with UK rules, and basically told the U.S. brass, “Your move.” After a “frank exchange of views,” the American authorities relented, Flight Lieutenant Ball got to keep his mighty mustache intact. The story made international news as a lighthearted clash of military cultures. As one report dryly noted, RAF rules at the time stated that while a mustache should not extend below the mouth’s edge, it can be “as wide as the bearer likes.” In other words, the British traditionally prized a good, broad mustache and weren’t about to snip theirs to appease foreign sensitivities. The episode highlights how a bit of facial hair can become a point of honor. For the RAF pilot, his handlebar wasn’t just personal grooming; it was an inheritance from a service where, historically, a man’s character could be measured in the boldness of his ‘stache.

RAF Lieutenant Chris Ball with his handlebar moustache

“Check Your Six (Inches)”: Camaraderie, Identity, and Esprit de Corps

Beyond superstition or protest, mustaches in the flying community have taken on a life of their own as symbols of camaraderie and aviator identity. There’s something about a group of pilots all growing mustaches together that builds a unique bond, a shared rite of passage that says, we’re on the same team. During Mustache March, this is exactly what happens: squadrons bond through friendly rivalry over whose ’stache comes in the fullest or most flamboyant by the end of the month. Aircraft maintainers, navigators, and other crew often join in too, uniting the whole squadron in fuzzy-faced fraternity. It’s hard to take oneself too seriously when sporting an absurd mustache, and that humility and humor break down barriers between ranks. In some units, Mustache March ends with an informal “pageant” where the best (and worst) mustaches are judged, prizes or dubious honors are awarded, and everyone shares a laugh, all of which strengthens team spirit. As the daughter of Robin Olds, Christina Olds, remarked after serving as a Mustache March contest judge, “The results have been entertaining, to say the least”. Entertaining indeed, but also bonding, those laughing faces belong to Airmen who trust each other both in jest and in battle.

Even outside of March, the deployment mustache has become a cherished tradition in many air units. On long deployments aboard ships or at remote bases, military aviators often let their mustaches loose as a mark of being “in the shit together.” Naval aviators, for instance, have a storied custom of growing a mustache during carrier cruises. It’s partly a boredom buster and partly a badge of honor for those who’ve trapped on a pitching carrier deck. “Basically, most of the male tailhookers grow mustaches as a way to have a friendly competition and build camaraderie among the Air Wing pilots,” explained one Navy C-2 Greyhound pilot. “When you’re on a ship for that long…growing out a mustache is one of the few things you can do to mix up your daily routine.” There’s even a bit of playful magical thinking involved, as he noted: “Some even say you become a better aviator and are bestowed with ‘God-like’ powers when you grow a mustache, so it behooves you to do just that.”

C.J. ‘Heater’ Heatley ‘Strawberry Top Gun’

Even when regulations force a quick return to a clean-shaven look, the camaraderie forged in the interim remains. Many an aviator has sheepishly admitted that after a multi-month deployment, the first thing they do upon returning home is shave off the scraggly mustache, sometimes at the insistence of a spouse who hasn’t seen their upper lip in ages! But by then the mission is accomplished: not just the military mission, but the bonding experience. Those pilots will forever share the memory (and embarrassing photos) of “the deployment ‘stache of 20XX,” a memory often accompanied by stories of close calls, practical jokes, and nights spent laughing in the mess hall. The mustache becomes shorthand for an entire chapter of shared life experience.

In Summary

The mustache is a tradition that pulses through hangars and ready rooms every spring. What began as a rebellious tribute to Robin Olds now brings together pilots, maintainers, and even spouses in a month-long, good-humored contest of follicular pride. Squadrons raise money for charity, compete for the best ’stache, and carry on a legacy that unites generations. It’s more than nostalgia, it’s a nod to the aviators who flew before, those who dared to bristle at authority and left their mark not just in the sky, but on their upper lips.

The aviator mustache has since entered the cultural bloodstream, reflected in everything from squadron traditions to Hollywood. When Top Gun: Maverick gave “Rooster” a mustache to link him to his fictional father, Goose, audiences didn’t just see character development; they saw a symbol. That thick upper-lip homage wasn’t just for style; it echoed a real tradition rooted in squadron camaraderie, risk, and rebellion. From WWI dogfights to carrier traps and combat deployments, the mustache remains an enduring mark of the military aviator’s spirit: part swagger, part superstition, all brotherhood. As long as there are pilots climbing into cockpits, there will be mustaches coming in hot behind them.

Leave a comment